Mongolian Collection

When the Ferenc Hopp Museum of Asiatic Arts was founded, there was no independent Mongolian collection. Its foundation was laid by the work of two experts: the first director of the museum Zoltán Felvinczi Takács, who, driven by his general interest in European and Asian Huns, strove to acquire objects from Mongolia from the very start, and Lajos Ligeti (1902–1987), a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and orientalist (expert in Mongolian studies), whose regular gifts resulted in the emergence of a separate collection. Later, in the decades following the 1950s, many possibilities opened to expand the collection. In 1965, János Kádár, General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party, presented the museum with the gifts bestowed upon the Hungarian governmental delegation during their official visit to Mongolia, which added a wealth of folk art to the collection. A set of objects representing Mongolian attire was given to the museum by Árpád Göncz, President of the Republic of Hungary. Countless additional objects were generously donated to the Mongolian Collection by Hungarian members of cartographic, geophysical, and hydrological expeditions to Mongolia in the second half of the century (1957–1990).

The Mongolian collection today boasts almost a thousand items, a substantial proportion of which are related to Mongolian Buddhist art, such as scroll paintings, woodblock prints, figurines, ceremonial objects, and religious books. Some are ethnographic, but the majority are works of applied art, dating predominantly from the nineteenth century, with just a few earlier relics.

The most valuable and unique section of the Mongolian Collection comprises the Buddhist scroll paintings, known by their Tibetan name of thangkas. These rectangular pictures, executed mostly in portrait format, were painted onto primed canvas and fitted with a textile frame, and after consecration, they were used in religious ceremonies. A typically Mongolian type of thangka is made with the appliqué technique, resulting in large scroll pictures assembled from pieces of silk and brocade, of which the museum’s collection holds a remarkable example.

The most outstanding figurines in the collection are associated with the School of Zanabazar. The Hopp Museum possesses figurines from the workshop connected to his school, which are characterised by rich ornamentation, delicate execution, faces with high-arched eyebrows and half-closed, lotus-shaped eyes, and raised lotus thrones.

The collection also boasts a large number of Buddhist miniature paintings (in Tibetan: tsak li), votive tablets (in Tibetan: tsha tsha), and Buddhist ceremonial objects. The Mongolian Collection contains around a hundred manuscripts and woodblock-printed texts from Mongolia, most of which are in the Tibetan language. Besides holy Buddhist scriptures, there are also short ritual texts, consisting of just a few sheets. The most valuable manuscript is the Mahayana Sutra, the Sutra of Great Liberation, written on black-lacquered paper using ink made from seven types of gemstones.

The collection contains a number of more unusual objects, such as a horsehead violin (in Mongolian: moriin khuur), which is a Mongolian national symbol, a reflex bow and its arrows, and figures from a Mongolian chess set. Among the objects of ethnographic nature, the costumes and accessories are present in the greatest number, but everyday objects of the nomadic lifestyle can also be found.

Objects of historical significance in the collection include some archaeological finds, a seal dating from the beginning of the nineteenth century, and a bilingual official document written in Tibetan-Mongolian.

Gallery

Mongolia, 19th century,

gilded bronze statue,

height: 21.8 cm

FEMALE BODHISATTVA

Mongolia, first half of the 19th century

Thangka, painted canvas and silk

Scroll painting with blue border, without wooden slat and rod

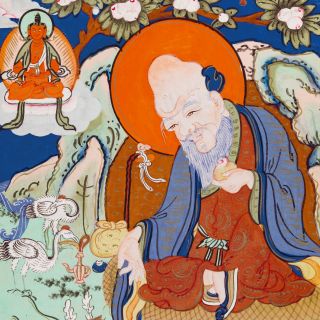

Mongolia, early 20th century,

paint on linen,

66.6×124 cm, 40×60 cm

(KHALKHA: CAGĀN ÖWGÖN)

Mongolia, early 20th century,

thangka, paint on linen,

27.5×21 cm

Mongolia, 19th century,

gilded bronze statue,

height: 15.6 cm

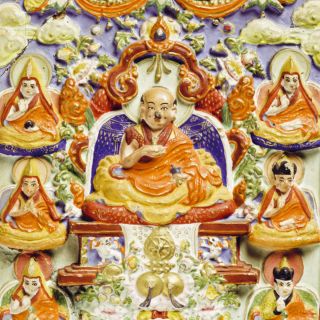

Mongolia, School of Zanabazar, 17th–18th century

Gilt bronze figurine

Mongolia, 18th–19th century

Thangka, painted canvas with silk edging

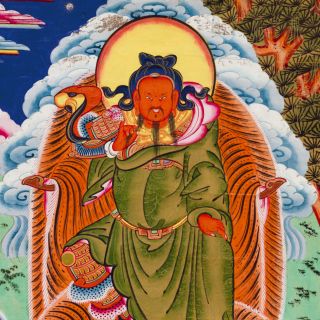

Inner Mongolia, early 20th century,

thangka, paint on linen,

43.5×62.5 cm

donated by Lajos Ligeti

Mongolia, 19th century

Appliquéd thangka, silk and brocade

Mongolia, School of Zanabazar, 17th–18th century

Gilt bronze figurine

Mongolia, early 20th century,

silver alloy, 15.5×18 cm

Mongolia, 19th century,

painted clay,

15×11.9 cm

Mongolia, 19th–20th century,

painted clay,

12×10 cm

Mongolia, 19th century,

thangka, painted on silk with mineral paints

and framed with a silk border,

48×82 cm

Mongolia, 19th century, bronze, silver,

diameter: 8.1 cm, height: 15.4 cm;

Mongolia, 1965,

length: 108 cm, width: 30 cm

donated by János Kádár, 1965

Inner Mongolia, early 20th century,

thangka, paint on linen,

70×54 cm

donated by Lajos Ligeti

Inner Mongolia, 19th century,

thangka, paint on linen,

70×53 cm

donated by Lajos Ligeti

THE BODHISATTVA OF COMPASSION

Inner Mongolia, early 20th century,

thangka, paint on linen,

71×52.5 cm

donated by Lajos Ligeti

Damaru ceremonial hand-drum. Mongolia, 19th century. Wood, canvas, silk, leather, cowry shells

Shinbone flute. Mongolia, 19th century. Human bone, painted leather

Ritual trumpet. Mongolia, 19th century. Brass and copper

Mongolia, 19th century,

metal and wood, 3×5 cm

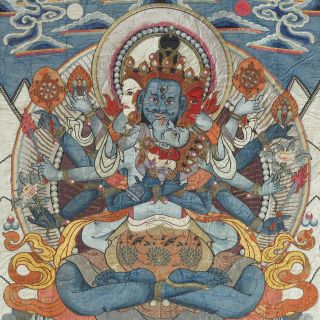

THE DHARMA PROTECTOR DEITY YAMI

Mongolia, 18th–19th century

Painted bronze

Mongolia, early 20th century,

wood, 18×26 cm

Mongolia, 19th century, metal, 9.2×11 cm

painted, wooden statue, with a monk’s silk robe

Mongolia, 19th–20th century,

height: 15.8 cm