Southeast Asian Collection

The foundations of the Southeast Asian Collection, just like the other collections, were laid upon the bequest of Ferenc Hopp, the person the museum takes its name after. He was so much enthralled by the tropics at the start of his first journey in Asia (1882–1883) when he visited the botanical garden of the Javanese city of Bogor (then known as Buitenzorg) that after his return to Budapest, he had his garden designed to recreate this atmosphere. His home on Andrássy Avenue also became known as the Buitenzorg Villa.

The youngest collection within the Ferenc Hopp Museum is the Southeast Asian Collection, which became separate only in 2014, as the objects belonging here were formerly part of the Indian / South Asian Collection. However, this collection produced the most dynamic growth in the last decade.

Initially, when the museum was established, less interest was shown towards the art of Southeast Asia, still the collection was constantly growing through gifts, bequests, and purchases. What is more, the museum’s first temporary exhibition, held in 1931, featured objects from Java from a private collection, curated by Zoltán Felvinczi Takács in consultation with Ernő Zboray, who possessed wide-ranging local knowledge of the island. It is also an undeniable part of the history of the collection that until the 2010s, objects from the Southeast Asian region were typically not highlighted in their own right but as an integral part of the Indian collection or as a group of a specific type of object (Javanese wayang).

It was the exhibition Nagas, Birds, Elephants. Traditional dress from Mainland Southeast Asia in 2016 and the centenary exhibition opening in the summer of 2019 that first acquainted the larger audience with the most important pieces of the collection of the region regarded as a cultural unit despite its diversity.

In terms of museology, the importance of the Southeast Asian Collection lies in the fact that it comprises not just disparate objects from different collectors, but also coherent groups of items. In 2014, more than 150 items, mainly textiles, ceramics, and small wooden carvings from Vietnam and Laos, were acquired from the collection of Ödön Rádai and his wife; in 2014–2015, the large Thai Buddhist scroll paintings belonging to Emil Delmár, which had been on loan to the museum for many decades, were finally purchased; and around the same time the collection was also enriched by three contemporary works by József Gaál, inspired by the Indonesian wayang objects exhibited in 2013. In 2016, at an auction held at a Budapest gallery, the museum acquired a Buddhist hanging scroll painting and some Buddhist statues that were formerly in the collection of Károly László.

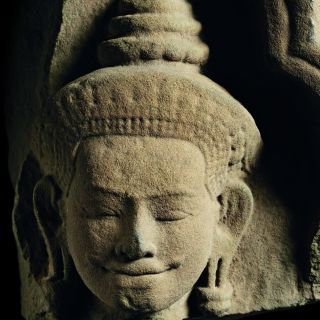

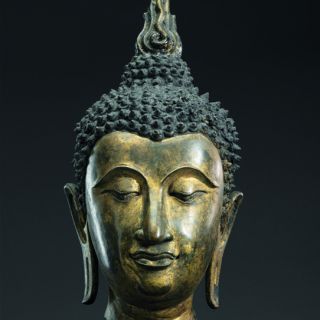

The collection is divided into two larger geographical sections: Mainland Southeast Asia and Insular or Maritime Southeast Asia. Artworks from Mainland Southeast Asia are dominated by Buddhist artefacts, with sculptures making up the largest share. One of the earliest pieces is a fragment of a Khmer carved sandstone relief, datable to the thirteenth century, which was a gift to the museum in 1940 from Bertalan Hatvany. Thai art, among others is represented by a lacquered and gilded Buddha head of exceptional quality from the sixteenth century, originally given to the Hungarian National Museum by Tivadar Duka and later transferred to our museum. Another example of the most impressive pieces comes from Béla Ágai and his wife, such as a seated Buddha in royal attire, dating to the turn of the eighteenth- and nineteenth centuries, and a Burmese/Thai guardian deity from the nineteenth century.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the museum’s collection further expanded thanks to Hungary’s relations with “friendly socialist nations”. At that time the majority of exchange gifts from the Southeast Asian region came from the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, comprising mainly woodblock prints. Furthermore, in 1961 the museum also received some precious Thanh Hoa ceramics from the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

Although the collection also includes few pieces from Malaysia and the Philippines, most objects from Insular Southeast Asia were made in Indonesia, particularly in Java. The largest self-contained subset of Indonesian objects is a more than fifty-piece group of (three-dimensional, wooden) wayang golek puppets, mostly made in the nineteenth century. These make up only half of the original collection, as the other half was passed to the Museum of Ethnography in Budapest. The pieces of the setting, together with the instruments of a gamelan orchestra, were also shared between the two museums.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the division of weapons which were in the focus of Ferenc Hopp's interest as a collector. The collection of weapons includes not only the magical-cultic daggers of the Indonesians, the variously crafted krises, but also the several head-hunter swords of impressive design (from the island of Kalimantan/Borneo), and the typical Sumatran and Philippine weapons as well, commemorating the adventurous life of their former owner.

Gallery

TWENTY-EIGHT BUDDHAS

Thailand, 1850–1870

Tempera on textile

From the collection of Emil Delmár

Cambodia, 13th century, Bayon style

Sandstone

Gift from Bertalan Hatvany

Myanmar (Burma),

second half of the 19th century

Lacquered wood

Collection of Károly László

Thailand, 16th century,

Ayutthaya period

Gilt bronze

Gift from Tivadar Duka

Myanmar (Burma) or Thailand (Siam), first half of the 19th century

Lacquered wood

Collection of Mr and Mrs Béla Ágai

WAYANG KULIT CIREBON)

Indonesia, Java, near Cirebon,

first quarter of the 20th century

Painted buffalo hide

From the collection of Ernő Zboray

Indonesia. Central Java. 10th century

Collection of János Xantus

Laos, 17th–18th century

Painted ivory

IN BHUMISPARSHA MUDRA

(RIGHT HAND TOUCHING

THE GROUND GESTURE)

Myanmar (Burma), late 18th century –

early 19th century

Lacquered wood

Collection of Mr and Mrs Béla Ágai

WITH CARVED UNDERGLAZE DECORATION

Vietnam, Thanh Hoa, 11th–12th century

Exchange gift from the Museum of History

of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam