Archive

The Hopp Museum Archive collects documents and photographs pertaining to the history of the museum, as well as exhibition documentation, the legacies of Hungarian travellers to and researchers of the East, and archival photos of Asia that are of artistic or historical value. Archiving at the Hopp Museum began in 1949 when an inventory was made of the museum’s document photos (photographic documentation of exhibitions, artwork and document photos used in presentations), resulting in the creation of the document photo archive, 90% of which consists of artwork photos. This kind of photos document changes in the condition of the artworks from the time they were acquired by the museum. The document photo archive comprises 23,355 items, and is now a closed collection, no longer expanded in this form. Another closed collection is the slide archive, containing over 5000 photographic slides, most of which are projectable slides of artworks, although this collection also contains 298 stereo glass slides taken in Constantinople (today Istanbul) and Asia Minor by Dezső Bozóky in 1905. Apart from the document photo archive and the slide archive, neither of which will be expanded in the foreseeable future, the Hopp Museum Archive also contains 3236 photographs connected to Asia, and 13,390 inventoried documents. They can be accessed for research via a relational database.

After the decease of the first director of the museum, Zoltán Felvinczi Takács, in 1964, the need arose to archive the documents and photographs stored on the premises of the Hopp Villa that once belonged to Ferenc Hopp and Zoltán Felvinczi Takács. According to the first inventory, the Hopp Museum Archive came into being in 1966. Until 1983, however, there was no single person with overall responsibility for the archive, and the tasks were carried out by the curators of the different collections. Methodical collecting within the archive began in 1983 with the appointment of the first dedicated archivist, Marianne Felvinczi Takács (1917–2000), daughter of Zoltán Felvinczi Takács, who set about systematically processing all the documents that came to light in the Hopp Villa, from cellar to attic. She also established the system by which the documents are still stored today.

The Hopp Museum Archive arranges items into approximately two dozen sections, organised according to the legacies of individuals or based on a given theme, the most important of which are listed below.

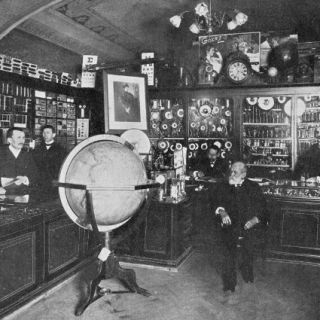

Ferenc Hopp (1833–1919), globetrotter, art collector, amateur photographer, establisher of the manufacture of teaching tools in Hungary, and founder of the Museum. The Hopp Museum Archive contains the largest number of documents (letters, postcards, prospectuses, photographs) for researching the life and collection of Ferenc Hopp and the history of the museum, including letters. Most of what survives of Ferenc Hopp’s extensive correspondence consists of letters returned to the sender, while letters have also entered the archive thanks to the heirs of Hopp’s erstwhile employees. The letters of Ferenc Hopp written in German are in themselves enjoyable accounts of his experiences during his five round-the-world trips, and they also provide valuable information about how Hopp’s collection developed. The documents Hopp amassed during his travels (prospectuses, maps, entry tickets, invoices, and the small printed materials he collected in a separate album during his journey of 1882–1883) are unique souvenirs from the period, of a kind that has rarely survived elsewhere. Ferenc Hopp, acknowledged by his contemporaries as an accomplished amateur photographer, gave seven albums of the photographs he took during his travels to the Hungarian Geographic Society, which were destroyed during World War II when the building housing the collection was hit by a bomb. All that remains of Ferenc Hopp’s enormous photographic collection are the photos, slides, and negatives that were left in the Hopp Villa.

Photographs by Hopp occasionally turn up in private collections, and identifying them is aided by the fact that Ferenc Hopp routinely signed his photos.

Also part of Hopp’s legacy, catalogues of the Calderoni company that are now in the Hopp Museum Archive are important documents concerning the history of manufacturing teaching tools in Hungary. István Calderoni was Ferenc Hopp’s father-in-law, and when the younger man later became the owner of the company, he kept the company name out of respect for his wife’s father.

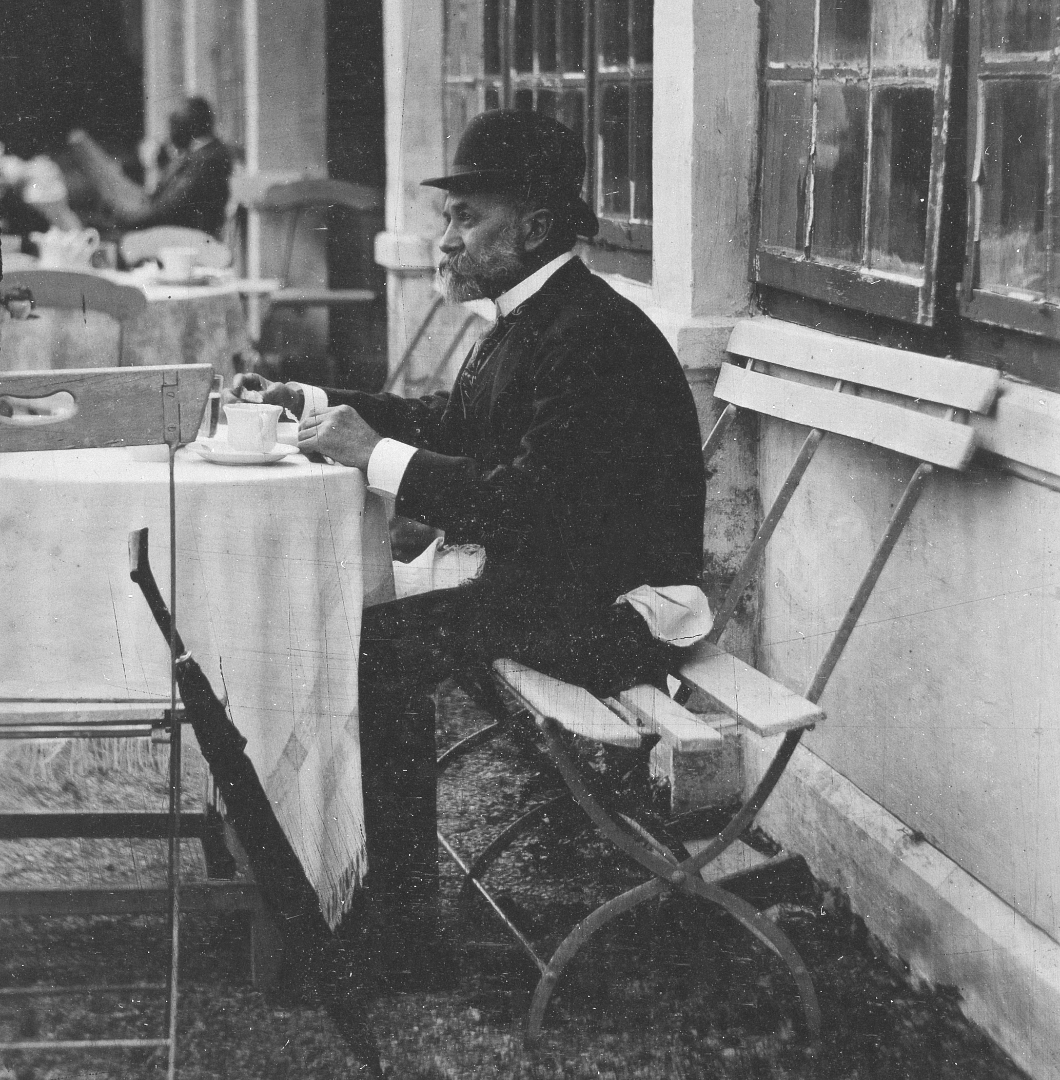

Dr Zoltán Felvinczi Takács (1880–1964), lawyer, art historian, researcher of the East, university professor, director of the Hopp Museum from its founding in 1919 until 1948, who continued to work for the museum until his decease (fig. 5). Besides his legal studies, he also learnt painting in Simon Hollósy’s school in Munich and studied painting and art history in Nagybánya (today Baia Mare, Romania) and Berlin. He began to deal with Eastern art in 1907, while preparing the oriental collection of Count Péter Vay for an exhibition. From this point on he kept a close eye on Hungarian collectors and collections of Eastern art and participated in organising exhibitions of such works in private hands, whilst remaining an expert judge of contemporary Hungarian art. Ferenc Hopp turned to him for expert advice when developing his own collection, and the friendship they formed played a key role in the formation of the Hopp Museum. Under the directorship of Zoltán Felvinczi Takács, the Hopp Museum functioned as a one-person institution, and he personally led the guided tours and held lectures, while he was respected by art collectors as the only Hungarian expert who was truly initiated in Eastern art. Zoltán Felvinczi Takács maintained contact with all of the most important Hungarian and foreign orientalists of the day, as well as archaeologists, museum experts, and art dealers. His legacy allows us to understand more about the main questions that concerned the archaeologists and art historians of the day, as well as their concept of and approach to Eastern art.

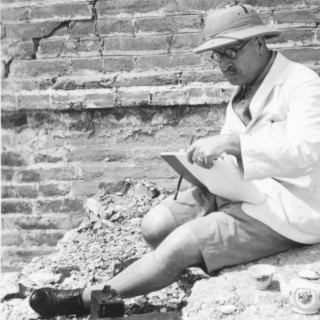

The large quantity of letters in the archive hints at his prodigious correspondence (with Albert Le Coq; Eduard Erkes; Giuseppe Tucci; John C. Ferguson; Georg Biermann). He also exchanged letters with the outstanding photographer and sinologist Ernst Boerschmann. Thanks to the friendships nurtured by Zoltán Felvinczi Takács, the museum’s collection was enriched with many exceptional artworks, as documented by his correspondence with art dealers (C. T. Loo; Géza Szabó; Bertalan Hatvany). His legacy is an essential source for the history of the Hungarian Society of Eastern Research (predecessor to the Csoma de Kőrös Society, the Turanian Society, and the Hungarian–Japanese Society, all three of which counted Zoltán Felvinczi Takács among their founding members. Further insight into the history of these societies is provided by the correspondence Zoltán Felvinczi Takács maintained with István Mezey, and Vikomt Nabeshima Naotora (1856–1925). Zoltán Felvinczi Takács wrote manuscripts, diary entries, and notes encompassing the entirety of Asiatic arts, and he wrote the first Hungarian summary of Asian art history, while devoting his life’s work to investigating the influence of Eastern art on Hungarian art. Besides his knowledge of art history, he also made use of the tools of archaeology, and he claimed that relics from the time of the Hungarian Conquest of the Carpathian Basin bore motifs from the Far East, preserved by their ancestors during their long migration, thus demonstrating a link between the culture of the steppe nations and the forms and motifs used in Hungarian art. The photos Zoltán Felvinczi Takács took on his journey to the Far East in 1935–1936 are also of documentary value, and his travel journal (published as Buddha útján a Távol-Keleten [On the path of the Buddha in the Far East]) is invaluable when it comes to interpreting the photographs.

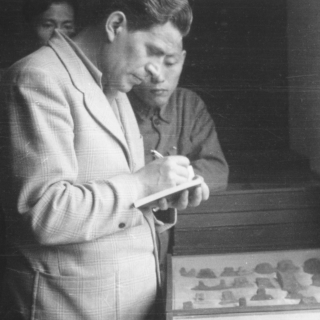

Dr Tibor Horváth (1910–1972), archaeologist, orientalist, art historian, director of the Hopp Museum from 1948 to 1972 . Besides his archaeological studies, he also earned doctorates in oriental history and the ancient history of Eastern peoples. He joined the Hopp Museum as an apprentice in 1939. In 1941 he earned a one-year study grant to Japan, but due to the outbreak of war, he did not return home until 1948, after more than six years in Japan, where he learned Japanese and dealt not only with local archaeology, but also with several areas of Japanese art and culture. Back home, in July 1948 he was appointed head of department at the Hopp Museum, and after Zoltán Felvinczi Takács’s retirement, he took over as director of the Hopp Museum, a position he held until his death. During his time as director, he laid the foundations of a modern national museum, and he considered it important for every area of the collection to be managed by a curator who knew the relevant language. Thanks to the large amount of travelling exhibitions that he organised with his colleagues, as well as the lectures he held both in the capital and in regional cities, Tibor Horváth turned the Hopp Museum into a major element of Hungary’s cultural scene. The archive holds documents originating from Tibor Horváth (letters, manuscripts, travel diaries with drawings, museum-related papers), which inform us about the status of museology in those days and the main scholarly questions that he and his colleagues dealt with, providing insight into almost a quarter of a century of the history of the Hopp Museum.

Dr Ervin Baktay (1890–1963), Indologist, art historian, writer and museologist, whose legacy was acquired by the Hopp Museum Archive in 2012. He initially studied to be a painter, but his literary work brought him early success. He lived in India from 1926 to 1929, where he attempted to earn a living from painting, but once again he was steered in the direction of literature, this time by the success of the Eastern Letters he wrote in India. On his return home, working as a freelance writer, he described his experiences in India in his travel books, illustrated with his own photographs, and in his lectures. The Hopp Museum Archive holds manuscripts by Baktay, including translations, short stories, poems, and stage works. Between 1946 and 1959 he was keeper of the Indian Collection at the Hopp Museum. Documents pertaining to his work at the museum, the manuscripts for his courses on Indian art and much of his professional correspondence (291 items) were acquired by the archive with his legacy. Baktay was among the first Hungarians to popularise the practice of yoga in Hungary, and in his astrological works he examined the common aspects of Indian and European astrology – manuscripts on this subject are also held by the archive. Ervin Baktay’s photographic collection (pictures of his trips to India in 1926–1929 and in 1956, family photos and portraits) comprises negatives and photos.

Simon Hollósy (1857–1918), painter, is immortalised with his pupils in a set of photographs that entered the Hopp Museum Archive as part of Baktay’s legacy. Baktay first attended Hollósy’s school in Munich in 1911, and until World War I he spent several summers at the master’s painting school in Técső (today Tiachiv, Ukraine).

The “Indian” life (meaning Native American in this context), the Western Games (sic!) and Symposiums. Role-playing games were an integral part of the lives of Ervin Baktay and his circle of friends, who began to organise “Indian camps” in 1931 in the village of Verőce, before continuing on Kismarosi Island from 1933 onwards. An unknown professional photographer took pictures of the “Indian” life; those taken between 1931 and 1936 (81 pictures) were arranged in two albums, while the others, taken later, remained unbound. The last pictures were taken in 1954. The clothes, utility items and weapons were made by the “Indians” themselves, following serious research. The Hopp Museum Archive holds charts Baktay drew using coloured pencils in preparation for the clothing and the bead decorations, as well as seven clothing ornaments decorated with beads. Between 1916 and 1939, Ervin Baktay and his friends held regular costumed parties in suitably decorated surroundings (Rome, Wild West, Russia). Around a hundred photos of these get-togethers also form part of the Baktay legacy.

Umrao Singh Sher-Gil (1870–1954), philologist, philosopher, a pioneer of Indian artistic photography, and brother-in-law of Ervin Baktay. During his stay in Hungary (1913–1921) he inducted both Baktay and Károly Fábri (1899–1968) into the basics of Indian philosophy and literature. Photos attributed to Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, included in Baktay’s legacy, now form part of the archive. Several photos have dedications or comments on the back. Many of the photographs are of Umrao Singh’s daughter, the painter Amrita Sher-Gil (1913–1941), mostly taken in family settings.

The Komor family of art dealers shared links with the Hopp Museum for several generations. Between 1903 and 1914, Ferenc Hopp purchased large quantities of artworks from the Kuhn and Komor Company or through George Komor, often paying in arrears (there are invoices and letters in the archive). In the 1930s and 1940s, Zoltán Felvinczi Takács corresponded with Mátyás Komor, György Komor, and Pál Komor. The museum director bought artworks with the mediation and financial support of Mátyás Komor, who also donated some pieces to the museum (the archive holds documents and informal letters originating from Peking, Shanghai, Yokohama, and Hong Kong). In 1948, Tibor Horváth passed on the greetings of Mátyás Komor from New York, and in the 1960s he received a notification from Mátyás Komor from Tokyo.

Dr Dezső Bozóky (1871–1957), physician, art collector and amateur photographer, who travelled to the Middle East and later to the Far East as a medical officer with the Austro-Hungarian navy. After his death in 1957, numerous artworks, as well as his substantial photographic collection, were bequeathed to the Hopp Museum.

Hand-coloured stereo glass slides made in Constantinople (today Istanbul) and Asia Minor in 1905 record the buildings and cemeteries of the city and its bustling urban life. Hand-coloured stereo photographs, hand-coloured slides and albums, all taken on his journey to the Far East in 1907–1908, are not only of aesthetically high quality but also document this period of history in an unparalleled way. Besides the photographic collection, the archive also possesses documents and souvenirs from his travels (maps, leaflets, and letters).

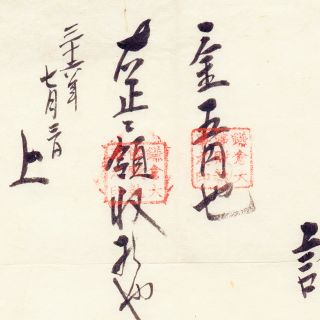

Dr Pál Miklós (1927–2002), sinologist, art historian, art writer, became acquainted with Chinese art while studying on a stipend in China (1951–1954). Having returned home, he was made keeper of the Chinese Collection at the Hopp Museum (1955–1957), and after spending a number of years in the Institute of Literary Sciences at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, he was appointed director general of the Museum of Applied Arts (1975–1984), and then director of the Hopp Museum (1985–1987). The archive holds documents (letters, manuscripts, postcards, translations) that are connected to Pál Miklós, who was the author of many of them. His descriptions of artworks reveal a high degree of scholarly knowledge, while his letters and his greetings cards not only demonstrate his skills at calligraphy but also preserve his acerbic wit.

Moritz Czikann von Wahlborn (1847–1919) was the first ambassador of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in Peking (Beijing). In 1963 the museum purchased photographs from his estate, all works by the professional Japanese photographer Yamamoto Sanshichiro.

In 2016 the museum bought further photos from Baron Czikann’s estate. Taken between 1897 and 1904, the pictures document the ambassador’s journey to China and the lives of diplomats at the time. Several scenes of Peking record the state of the city after the Boxer Rebellion was defeated in 1901. The collection includes a few formal photographs, as well as several that were taken by Alfons Mumm von Schwarzenstein, ambassador of the German Empire and also an accomplished photographer. The amateur photos in the collection, which are not always technically faultless, are nevertheless valuable contributions to our knowledge of people’s everyday lives in China at the time.

Catholic missions operating in China are documented in the Hopp Museum Archive by a set of negatives taken around 1931 at the Hungarian missions in Daming and Guizhou, which were received as a gift from the Hungarian Museum of Photography in 2002. The pictures used by the theologian and teacher József Waigand (1912– 1993) for his lectures on the history of church missions, consisting of colour slides of Catholic Peking (Beijing) and rolls of projectable slides, on oriental religions, made in the 1930s, were purchased by the museum in 2008.

Lokesh Chandra (1927), art historian, compiled the Dictionary of Buddhist Iconography (New Delhi, 1999). In 2006, the Hopp Museum Archive took possession of the entire manuscript of the dictionary, supplemented with photocopies, photographs, negatives, woodblock prints, and colour prints, as a gift from the author.

Hungarian doctors in the Korean War. In 2006, Tibor Heltai donated to the Hopp Museum Archive unique documents, photographic tableaus, and photographic negatives of the work and lives of Hungarian doctors in Korea between 1950 and 1957.

Károly Rainer (1875–1951), architect, produced large glass slides documenting Japanese architecture after the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923.

Miklós Rév (1906–1998), photographic artist, travelled to China in 1955, to Tibet in 1956–1957, and to Vietnam in 1959–1960. The photographs and negatives taken during his journey to Vietnam were presented to the Hopp Museum Archive in 2005 as a gift from the Hungarian Museum of Photography.

Sir Aurel Stein ( 1862–1943), Hungarian-born British archaeologist, was a young scholar, aged around 25, when he wrote a letter of thanks to Ferenc Hopp, which is now in the archive. Stein’s relationship with the Hopp Museum continued throughout his life, and the correspondence between him and Zoltán Felvinczi Takács reveals a dialogue undertaken by two researchers sharing mutual respect and an interest in scientific matters. The extraordinarily polite letters Stein wrote to Ervin Baktay resonate with the voice of an elderly master, encouraging Baktay to pursue an academic career.

Imre Schwaiger (1868–1940), Hungarian-born British art dealer, known as the unofficial “second founder” of the Hopp Museum, made many generous donations to the museum between 1914 and 1939, contributing greatly to the expansion of the Indian, Nepalese, and Tibetan collections. Zoltán Felvinczi Takács, with his vast expertise, was probably partly responsible for the fact that Schwaiger’s gifts filled gaps in the museum’s collections, helping to ensure that the Hopp Museum developed in a comprehensive, scientific direction. The archive contains letters Schwaiger wrote to Felvinczi Takács, as well as documents related to Schwaiger’s activities.

Dániel Szilágyi (1831–1885), a Turcologist who became renowned for his role in arranging for books once belonging to the Corvina Library of King Matthias to be returned to Hungary, and a book dealer who moved to Constantinople (today Istanbul) after the failed Hungarian Revolution of 1848–49, who learned Turkish, Arabic, and Persian. With his collection of books a set of photographs also returned home: pictures of the pages of Persian albums, which joined the Hopp Museum Archive in the 1950s. The photographs produced by Pascal Sébah (1823–1886) in his studio in Constantinople (before 1885) were the first to reveal to the wider world the picture collection concealed within the Topkapi Saray, and even in the first decade of the twentieth century, these were the only images available of the sultan’s collection.

Pál Teleki (1879–1941), geographer and future prime minister of Hungary, was friends with Zoltán Felvinczi Takács in their youth. The 70 Teleki documents in the Hopp Museum Archive and the 16 letters he wrote to Felvinczi Takács are important sources about Teleki’s work and the activities of the Hungarian Geographical Society. The earliest document related to the museum, dated 1911, was a letter Teleki wrote to Ferenc Hopp thanking him for a financial donation. Teleki’s photographs of the architectural relics in Konya, Turkey, are unique records of how the city looked in the 1910s. The archive also holds the majority of the printing plates for Teleki’s Atlasz a japáni szigetek cartographiájának történetéhez [Atlas of the History of the Cartography of the Japanese Islands], published in 1911.

Ferenc Zajti (1986–1961), painter, theologian, researcher into the relationship between the Hungarians and the Scythians, who tried to find the “Huns of Gujarat”, purported relatives of the Scythians, during his trip to India in 1928. From 1933 to 1946 he was chief librarian of the Eastern Collection of the Budapest Municipal Library. In 2007, his heirs donated to the Hopp Museum Archive documents from his estate, as well as tableaus from the 1929 exhibition, publications and newspaper cuttings (some in identical duplicates), archival photographs and negatives. Zajti’s documents contribute to the history of early twentieth-century research into the origins of the Magyars, the history of the Hungarian-Indian Society, and research into the history of ideas. Some of the negatives in the collection are family pictures or studio photos documenting Zajti’s work as a painter. Other negatives and photographs originate from Zajti’s trip to India in 1928. Ferenc Zajti’s estate also included the legacies of two researchers into Hungarian origins: Kálmán Némäti and Jenő Tóth. The photos in the Zajti collection that can be dated to 1911 or earlier probably derive from the legacy of Jenő Tóth.

Kálmán Némäti (1855–1920), teacher, writer, librarian, researcher into the origins of the Magyars and editor of the first Turkish-Hungarian, Hungarian-Turkish dictionary. Documents from his estate are now in the archive, alongside negatives of photographs taken of his manuscripts.

Jenő Tóth (1882–1923), painter, carried out linguistic research, and his documents on this subject are now in the Hopp Museum Archive, together with drawings and watercolours recording motifs from India, which he made on the subcontinent between 1907 and 1912. The documents and motif collection were acquired as part of the legacy of Ferenc Zajti. Both men based their research into the relationships of Hungarian language and the ancient history of the Hungarian nations on similarities in phonetics and decorative motifs.

World War I exerted its impact on the lives of orientalists as well, traces of which can be found in the collection of the Hopp Museum Archive, in the form of postcards and letters written from the frontlines and prisoner-of-war camps by several friends and acquaintances of Zoltán Felvinczi Takács. Numerically the largest group consists war camp postcards written by Japanologist, István Mezey, which track out his fate from the POW camps of Siberia to Japan. The collection also holds postcards written by the philosopher, orientalist, and Buddhism expert Jenő Lénard (original name: Eugen Isak Levy), by writer Marcell Vidor, others by lawyer Gyula Ribiczey, and the photograph-bearing letter of Pál Teleki. Surprisingly, the cards sent from the front, from POW camps, or from military hospitals only mention the events of the war in passing, and focus mainly on questions to do with oriental studies or art. The collection is supplemented with official and amateur photographs from the legacy of Ervin Baktay, together with photographs and postcards from Lajos Schöne, a former employee of Ferenc Hopp.

Gallery

Changsha, China, 29 October 1954 Gelatin silver print

Kamakura, 3 July 1903.

FERENC HOPP WITH FOUR MEMBERS OF HIS STAFF

in the business premises of Calderoni and Company on Gizella Square, Budapest,

with a large globe in the foreground and a large photograph

of Empress Elisabeth of Austria (Sisi) in the background,

ca. 1900

22 July 1906

PORTRAIT OF DEZSŐ BOZÓKY

Gelatin silver print,

ca. 1905

THE DAMAGE ON THE BANKS OF THE SURU RIVER

Between Kargil and Saliskote, Western Tibet, 29 August 1928

Printing-out paper

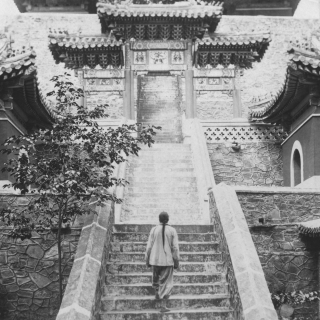

TEMPLE OF THE BLACK DRAGON POOL (HEILONGTAN)

Near Peking (Beijing), China, ca. 1900

Albumen print

THE CHINESE GIRLS’ SCHOOL IN SINGAPORE

Singapore, late 19th century

Gelatin silver print

From the photo collection of Dezső Bozóky, 1907–1908

Nankou Pass, near Peking (Beijing), China, 31May 1936 Gelatin silver print

Curio

The Curio-blog explores the hidden treasures of the Hopp Museum Archives. By selecting among the curious products of its virtual showcase, the blog offers a taste of the museum's inexhaustible collection of background documentation (manuscripts, correspondence, documents, brochures, and archive photographs) related to the written heritage and tangible artefacts of its collections. In the spirit of Ferenc Hopp, the aim is to share the knowledge of the themes highlighted in the collection and to show the connections between the different types of objects. We wish our blog to be an intellectual adventure and a source of joy for visitors of the site!

-

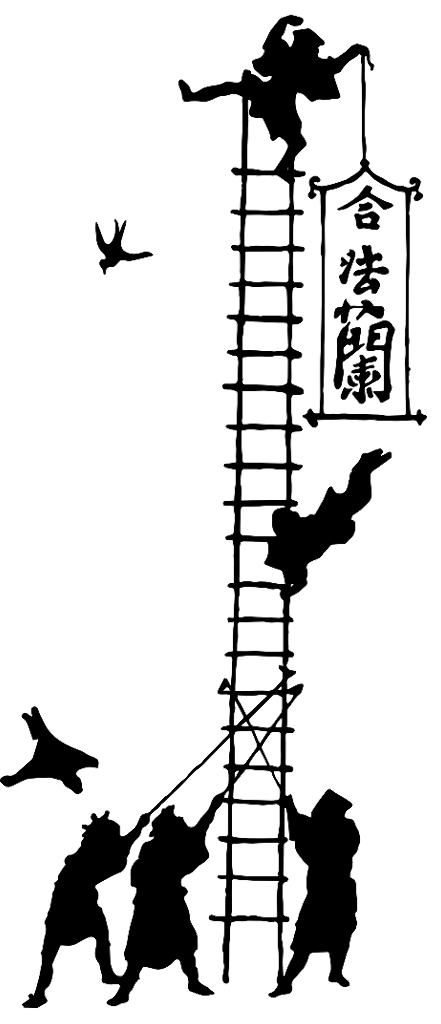

The Conciliatory Cape

The aim of the present article is to present the significance and functionality of the raincoat in the religious life of the Far Eastern societies, as experienced nearly 115 years ago by Count Péter Vay (1863-1948), missionary and Asia explorer; and Dr. Dezső Bozóky (1871-1957), naval surgeon of the Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Navy, globe trotter and collector, during their voyages to Japan. Parallel to the documents of the time, which have now become the subject of museological research, the survival of the raincoat as a ritual object will be further examined as a result of my cultural anthropological fieldwork in 2012. More ❯❯❯

For a Permanent Record of the Matter

In Memoriam Hopp Ferenc

On 28 April 2023 we are celebrating the 190th anniversary of Ferenc Hopp's (1833-1919) birthday. Our short video presents a collection of photos and postcards from his travels around the world. Let this virtual memorial serve as an eternal memory of the attitude formating activity of the art collector and museum founder Ferenc Hopp, who enriched the intellectual heritage of Hungary and the world.

© 2022, Ferenc Hopp Museum of Asiatic Arts