Sanghay – Shanghai. Parallel Diversities between East & West

The new exhibition at Ferenc Hopp Museum of Asiatic Arts, titled Sanghay – Shanghai. Parallel Diversities between East & West, links the emblematic oriental metropolis of Shanghai with the Sanghay Bar in Budapest, a perfect encapsulation of the contradictory image of the East that prevailed in Hungary between the wars. The aim of the exhibition is twofold: firstly to allow a glimpse inside the world of Hungarians who lived and worked in Shanghai in that period, as seen through their own personal items (many of which now form part of the collection of the Hopp Museum); and secondly to present the findings of recent research into previously unexplored areas of Hungarian art that came under the influence of the East.

The latest research has uncovered a complex web of interconnections and mutual influences, not only in the different branches of the arts, but also in the most diverse areas of everyday life. The exhibition offers insight into the way people lived in Shanghai’s “Hungarian colony” in the interwar period, in streets that pulsated with workers and merchants from every corner of the globe! The sights of the city are brought to life in archive photographs and through the objects people used on a daily basis. In the photos taken by Imre Farkas, Western faces look out at us, posing in front of Eastern backgrounds, while in the postcards collected by György Román (artist, boxer, failed chocolate manufacturer and impresario) we can see oriental ladies dressed in fashionable Western clothes and accessories.

Among the Hungarians who tried their luck in the bustling Chinese city were members of the Komor family, who opened the Komor and Kuhn art dealership here and who, in the hard times at the end of the First World War, provided financial support to Hungarian soldiers and refugees trying to make their way home. The escaped prisoner-of-war László Hudec, a qualified architect, also settled here, eventually designing Shanghai’s first skyscraper. A selection of the buildings designed by Hudec that are still standing today are shown in a special photo installation. In addition to the permanent residents in the “Hungarian colony”, numbering some eighty families, many others paid briefer visits: tourists, secret agents (Trebitsch-Lincoln), and performing artistes, touring the entertainment hotspots of Asia.

The 1930s saw a profusion of new nightclubs in Shanghai, elite ballrooms that even welcomed female guests! More than one of these venues played host to a dancer named Flóra Dessewffy, completely forgotten by history until quite recently, whose varied performances also featured a few Hungarian dances; the scintillating costumes she wore, handmade in China, constitute one of the revelations of this exhibition. (Another widely travelled Hungarian performer, Klári Csorba, was often invited to sing live on Shanghai radio, and she may have been responsible for turning the world-renowned Gloomy Sunday into a hit in China.)

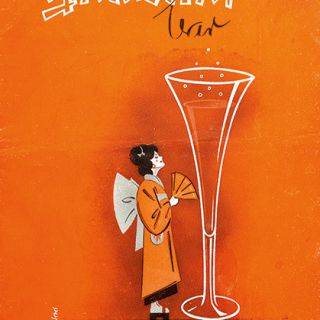

The modern cosmopolis of Shanghai contrasted sharply with the rest of China at the time; in 1937 a modest reflection of its magnificence was recreated in Hungary, when the Sanghay Bar opened its doors in Buda, not far from the Gellért Hotel. The nightclub was decorated in “marvellous eastern splendour”, and its name – together with countless little details, like the tiny, kimono-clad figure shown on the cover of the programme, alongside a champagne glass – was part of a concept designed to satisfy the growing local demands for a taste of the exotic. Now completely forgotten, it was once one of the most notorious night spots in town, famous for the varied entertainment provided by the dancers and musicians who performed there, on a stage dominated by an enormous statue of the Buddha.

As the paintings and photographs in the exhibition show, it was quite common during this period for dancing and erotica to be mixed together with elements from Asian religions, and such motifs were also found in cinema, the most popular and exciting art form of the day. In the early 1940s, two Hungarian film productions reworked the story of Mata Hari, the infamous oriental dancer and spy; the sets for both movies – Siamese Cat and Machita – included interiors decorated with items borrowed from the Hopp Museum, mostly Chinese and Japanese artworks. Excerpts from the films, in which the two stars – Zita Szeleczky and Katalin Karády – perform oriental dances, can be seen at the exhibition, as can some of the actual objects visible in the backgrounds of the movies.

The strange combination of erotica and Buddhism is evident in a number of works by some noted Hungarian artists, including Nirvana by István Csók and the famous series by János Vaszary titled Buddha with Nude. Pride of place in the exhibition is taken by a tapestry of the Buddha, a unique creation designed by Tibor Boromisza, a devoted student of Buddhism.

In addition to 88 digital photos, 3 film excerpts and over 200 artworks, there are also several interactive “do and learn” features at the exhibition. The richly illustrated catalogue, published in English and in Hungarian, contains studies written by twenty different authors on subjects as diverse as film history, dance history, architecture and the history of fashion.

In addition to the exhibits themselves, on display until 8 April 2018, a varied programme of related events is also planned, including a series of presentations on cultural history, an architecture day, themed workshops, a monthly Shanghai film club, and a range of museum education activities.

Curators: Dr Györgyi Fajcsák and Dr Béla Kelényi