I feel tea in my mouth. It is refreshing and dewy

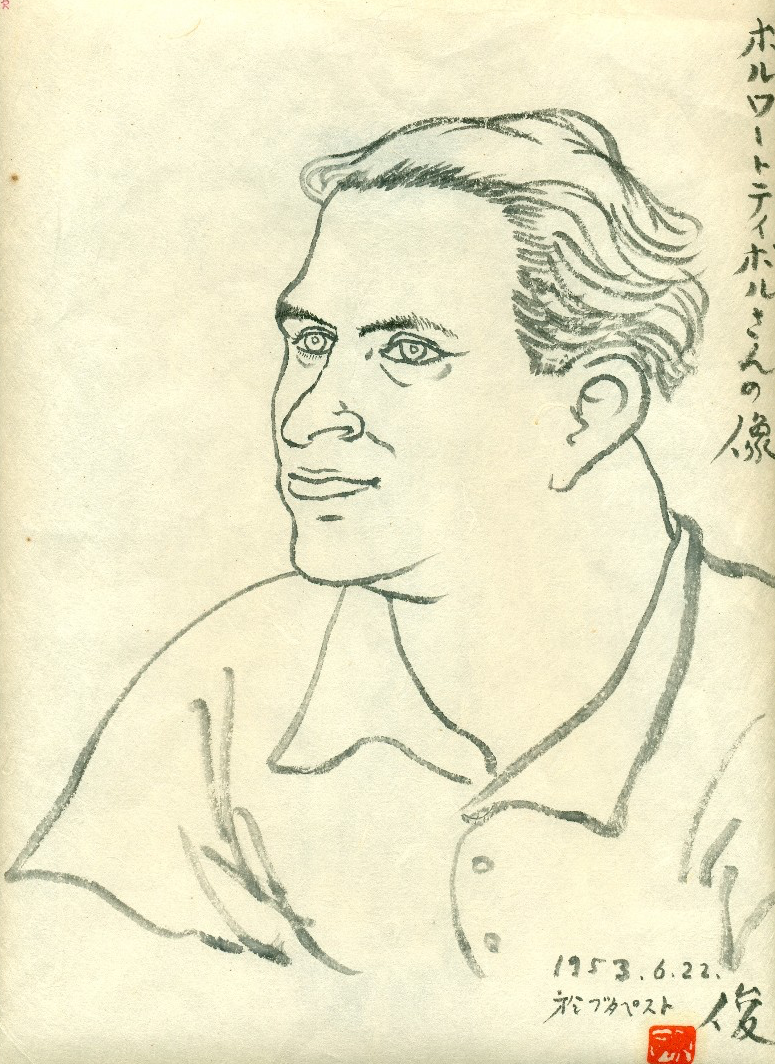

IN MEMORY OF TIBOR HORVÁTH

Picture 1.

(thirty-fourth of the The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō).

Japanese Collection, collected by Péter Vay,

inv. no. HFM_6459.

Prologue

Tibor Horváth (09 March 1910-31 March 1972) archeologist, orientalist, art historian, director of the Ferenc Hopp Museum from 1948 until his death in 1972. On the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of his death our museum organised a commemorative conference (Friday 29 April 2022) held at the Schickedanz Room of the Museum of Fine Arts. Emphasis was laid on the scientific approaches related to the comprehensive exhibition of Mongolian art Yurts and Monasteries and on the work of our director Tibor Horváth who deceased fifty years ago. The conference was organised by the curator of the exhibition, Tímea Windhoffer, who also made a presentation entitled Dr. Tibor Horváth in Mongolia. Tibor Horváth’s life was presented in detail by the former curator of the Hopp Museum Archives, Tatjána Kardos. The conference was followed by a short naming ceremony related to the inauguration of the Tibor Horváth Reading Room. The reading room was opened for the public by Dr. Györgyi Fajcsák, director of the Hopp Museum. Originally it was our late donor Mrs. Ferenc Lányi, born Kató Szegő (1920-2022), who suggested naming the reading room after Tibor Horváth. In the history of the Hopp Museum the largest donation received from a private donor came from of „Aunt Kató” – as everyone in the museum called her. Due to her noble generosity, and in memory of Tibor Horváth, the Moon Gate standing in the garden of the museum was restored in 2022. At the same time the modernisation of the library’s reading room also started. The naming ceremony of the reading room was organised as the last step of this process in the framework of the Memorial Year of Tibor Horváth and commemorating the noble personality of „Aunt Kató”, who deceased this year, in 2022.

Due to Tibor Horváth’s extensive work as researcher, archeologist, and museologist, 522 documents forming a historical collection can be found at our Archives, which include letters, manuscripts, travelogues with drawings, and documents of the everyday life of his work at the museum. He considered it of primary importance that the curators of the museum’s collections spoke the language of the given region. It is to his credit that the museum became one of the most important agents in Hungarian cultural life. The aim of the present article is to present the less known side of Tibor Horváth’s personality, which, however, formed an integral part of his multifaceted character.

|

Picture 2. |

Tibor Horváth was technical editor of József Attila’s paper, Szép Szó (the title meaning Nice Words), in 1936. He worked in the Hopp Museum as a trainee, unpaid from May 1939 and paid from December 1941. At this time, most certainly in recognition of his hard work, he was awarded the very first scholarship in the framework of the Hungarian-Japanese exchange programme of the National Scholarhip Committee in order to fund his study trip in Japan.

Tibor Horváth started his research in Japan in 1941. His letter to Zoltán Felvinczi Takács written on 6 August 1944 (inv. no. HFA_A.2907.1.) told about his forced moving together with the Hungarian embassy a hundred kilometers away from Tokyo, in Hakone Miyanoshita. His study trip planned for one year finally lasted until 1948 due to World War II. His scholarship was granted until 1944 but there are no extant documents on the following years. He became good friends with Ferenc Haár photographer (1908-1997) in Hakone Miyanoshita. As Magdolna Kolta, Károly Kincses, and Tom Haar stated in their book Haár Ferenc magyarországi képei (Hungarian photographs of Ferenc Haár), every foreigner was expelled from Tokyo after Pearl Harbor. Hungarians were considered neutral, therefore, they were forced to stay in a restricted area.

Tibor Horváth finally arrived home in July 1948 via the United States and Paris. He continued his work at the museum first as head of department, while after the retirement of the first director of the museum, Zoltán Felvinczi Takács, as director.

Following the dewy path or the mission of the voice of tea: In the footsteps of the tea masters Tibor Horváth, Kornélia Rajzó-Kontor, and Éva Kovács (Hamvaska)

In 1958 Tibor Horváth published his article about the art of tea Chadō to Chajin: The Tea Ceremony and Tea Masters in Acta Historiae Artium: Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae (pp. 223-239). Two typed copies of the Hungarian version of this article are stored at the Hopp Musem Archives (inv. no. HFA_A.3604.3.) and Library (Fü 940 / 7076). The Hungarian title is Chadō to Chajin: A Teaszertartás és a Teamesterek. As far as I know, Tibor Horváth was the first Hungarian tea master who had the chance to perfect his skills at the Kyoto school of the Mushanokojisenke branch of the Japanese tea school founded in the sixteenth century by Sen Rikyu (1522-1591). In the 1990s, the first tea master representing the Urasenke school of the Ancient tea school began to make regular visits to Hungary in order to teach. Among the hidden treasures of the Hopp Musem Archives, the past of Tibor Horváth as tea master still awaits to be uncovered and researched. What is more important to us, Kornélia Rajzó-Kontor, artistic director of the Hungarian branch of the Japanese Urasenke tea school and vice-president of the Japanese Tea Society of Hungary, discovered the origin of the Hungarian branch of the organisation Urasenke Tankokai in Tibor Horváth ’s past.

The beginnings are thus evoked by Tibor Horváth:

„The author of this paper [i. e. Tibor Horváth] learned tea ceremony from Sone Tsunemitsu, a teacher of the Mushanokoji (Kankyuan) school in Kyōto from 1942 to 1944. His master was very kind to him and invited him to the tea-parties (chakai)held on the 7th day of every month in the Ginkaku-ji. he could have also participated in the ceremonies arranged by his school in the different chapels of Daitoku-ji and other places. He is much obliged to the headmaster of Mushanokoji (Kankyuan), Sen Sōshu, for his advice and patronage. The author also owes much to Kanda Matsunosuke who was the curator of the industrial art section of the Kyōto National Museum, and who untiringly helped him in his studies not only in the museum but also in the late evening hours, in his friendly home. His thanks are also due to Sugahara Hisao (Kamakura, Tokiwayama Bunko) whose friendship dates from 1956-47, and his given much help and encouragement up to the present day.”

As for Kornélia, thanks to the exhange programme of the Rotary Club she spent one year in Japan in 1998 when she was seventeen years old. Here, at a musical event, she met Hirano Sōryō Takie, tea master of the Omotesenke school of the tea school founded by Sen Rikyu: it was her who introduced Kornélia in the secrets of the art of tea. In accordance with the rules of Rotary Club, she was hosted by a different family in every three or four months: first, she was accomodated by a civil servant and his wife, then moved on to the home (temple) of a monk, and finally was put up by the family of a doctor. Pursuing her interest, she gained first hand experience of Japanese everyday life and got to know the place and role of tea in community life. Beside practicing tea art, in her free time she also learnt how to wear a kimono and practiced calligraphy, ikebana, and martial arts. After finishing university she returned to Japan as scholarship holder of the head of the Urasenke school of tea, grand master Sen Sōshitsu Zabōsai, and entered the group of those few who could recieve education to become tea masters at the Urasenke Gakuen Chadō Senmon Gakkō, the institution of tea master formation, unique in the whole world. When it reached the fourth generation, the tea school founded by Sen Rikyu in the seventeenth century was divided in three branches led by his descendants. Tibor Horváth studied at the Mushanokojisenke school; Kornélia’s first master belonged to the Omotesenke school; while she became the grand master of Urasenke school in Hungary. International expansion and the establishment of foreign departments were the results of the missionary activity of the grand master of the fifteenth generation, Sen Genshitsu Hōunsai Daisōshō. His father, Tantansai created the organisation Urasenke Tankōkai in Japan in 1940, which became registered by the Japanese Ministry of Education and Culture in 1953. The first foreign department was created in Hawaii in 1951, while the first European division was founded in Rome in 1969. Sen Genshitsu Hōunsai Daisōshō visited Hungary twice, in 2005 and 2009. His visits made in order to improve diplomatic relations contributed largely to the broader recognition of the work of the Hungarian Urasenke department and the increasing interest in learning tea art. In response to these growing demands and based on her studies in Japan, Kornélia assembled the curriculum of the tea ceremony courses held at the Urasenke school in 2010.

Tibor Horváth wrote the following about the significance of tea ceremony: „The tea ceremony has occupied a highly important place in the culture and art of Japan beginning with the fifteenth century, and extending over a long period of development. This ceremony still survives and is an important factor in the upkeep of traditions and the cultivation of discriminating taste, […].”

Éva Kovács (Hamvaska) spent the academic year 1999-2000 in Beijing in order to learn Chinese as an exchange student of the Gate of Dharma Buddhist College. In 2003 when she walked the Ancient Tea Horse Road, with her knowledge of Chinese she helped out someone buying tea who repaid the favour with tea. In Hamvaska’s words, this was the moment when tea and chan crossed each other’s path in her life. Up until today, for almost twenty years, she has been using the very same kettle for making tea that she has bought there. Chinese tea art forms an integral part of her identity.

In September 2011 she travelled to Kunming and studied at the Pu’er Department of the Yunnan Agricultural University. She had her training in the framework of the Seed Propagation Programme of the Agriculturual Ministry of China at the Education and Experiment Base of the Yunnan Agricultural University and the Yunnan Simao Center for Tea Seed Propagation and Breeding. Parallely to this, she also recieved a formation of tea master organised by her department: at the end of her studies, she acquired professional qualification as tea master. She had the excellent opportunity to recieve education in the ancient land of tea, in Yunnan. According to one of Hamvaska’s teachers, Professor Zhang Sunmin: „trees growing wild in the south western part of Yunnan most probably developed through the third generation of bigleaf and Chinese magnolias. […] As the leaves of bigleaf magnolias have turned up in the district of Simao city, this suggests that the most ancient cropland of tea tree is the south eastern rergion of Yunnan.”

Hamvaska continues to express her gratitude that due to this school, she managed to find the roots of tea. As I got to know from her, peoples living near the tea trees used tea for healing at first, therefore, the tea masters were also doctors. The different peoples living in the territory of the Chinese Empire used different spices for seasoning tea: sometimes it contained orange peel, sometimes it was drunk with alcohol like in the case of the Naxi people, or „tea prepared three ways” of the Bai people is also known. The definition of the latter is given by Hamvaska this way: „The first is bitter, the second is sweet, and the third is what you will always remember.” What this really means will turn out from her forthcoming book on tea art.

After the spread of consuming loose leaf tea, from the tenth century onwards there developed the method of whisking tea, still used in Japan. „Here tea is first smoothly powdered, then hot water is poured on top with a special ladle used for this purpose, finally it is whisked with a bamboo whisk.” In China, however, it remained the consumption of loose leaf tea that was passed on from generation to generation: tea was prepared keeping its original taste, without seasoning. According to Hamvaska, this brought about a new phenomenon, the „tea contest”, when tea masters had the chance to test their skills and compete whose tea is more delicious.

Tibor Horváth’s article describes in detail how tea ceremony is built up:

„What is the tea ceremony? It is the preparation and drinking of tea in powdered form in a room and surroundings appropriate for the ceremony, in the presence of no more than four or five guests, who concentrate on the preparation and tasting of the tea, on the ustensils which are necessary to the tea ceremony, and on the decoration of the alcove (tokonama). The conversation schould be confined to the discussion of the beauty of these things. For the tea master-host, the social gathering (chakai) may take many hours as the groups follow each other, but for the individual guests it lasts no more than an hour, excluding the waiting.

Only the initiated would know the long history and careful preparation which is concealed behind the smoothness of the ritual and the simplicity and immediateness of the atmosphere.

The tea ceremony in its aspirations is very closely related to the teachings of the Zen sect of Buddhism, representing the closest kinship with Nature, the simple, active way of living which does not scorn manual labour; the acknowledgement that intuition, coupled with consciousness, can also be helpful in acquiring knowledge; the belief that sudden enlightment might help us to understand the substance and inner relations of phenomena.”

When I asked Kornélila the question what Japanese tea art and its acquisition mean to her, the most important factor she mentioned was her relatedness to the Sen family and the community, and adapting the set of values represented by tea art in everyday life. Every welcoming of guests is unique and unreplaceable. Learning tea art is a very long process, similar to how performing artists are trained: for a violoinist, for example, the first is to learn how to use the instrument. This step is the use of bowl, bamboo spoon, whisk etc; after this, there come the scale, utterance, playing short pieces, that is, tying the small „steps” together into a larger movement. The process starts with the larges movements of the host’s entering the room and sitting down on tatami, followed by smaller moves of putting tea powder in the cup, pouring water on top, and preparing the whisked drink. During these movements, the tea master pays attention to „utterance”, namely the rhythm of steps, the whisper of the silk kimono while moving, or the volume of the soung of water drops. The next level means learning and performing the plays of different composers with harmoniuous sounding and artistic values: in case of tea ceremony, this involves learning as many processes of welcoming guests specified by grand masters as possible. This way, the tea master as host becomes capable of serving guests most suited to the given circumstances. The artists breathe together with their guests and impress all their senses.

The aim of the tea master is to create calm, peaceful moments and to provide artistic experience and value for guests.

In his writing, Tibor Horváth underlines the importance of zen in creating harmony:

„In the practice of the tea ceremony, the influence of Zen is especially evident in the appreciation displayed for the hanging scroll (kakemono, a painting or a calligraphy), the vase with its flower arrangement, the tea-kettle, the tea-cups and other requisites of the ritual. According to the principle taught and required, the spectator should concentrate his attention to the upmost point where his spiritual condition could attain absolute identification with the object.

In the West too, there is nothing remarkable in one becoming completely absorbed in an object of art, a musical composition, an exciting book, a painting or statue, or self-identification with a role in a drama, especially on the part of the actor.”

When I asked Hamvaska about the relationship between tea and zen (chan), she gave the following answer: tea and zen (chan) support each other. What is more, like Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism are also present in tea. During the time of Cultural Revolution (1966-1977) there were seven things that were proclaimed to be indispensable and considered as sustaining life in China: firewood, tea, rice, oil, salt, soy sauce, and vinegar. It was present even in time of distress for healing, for welcoming guests, even if sometimes they could not afford it. During the preparation of tea, the lifeless becomes alive.

If someone has the opportunity to work and study at a tea plantation, they can pick tea leaves with their own hands which afterwards revive them. This revival creates different perfumes. The tea masters can get to know their inner selves they have not known before. If they prepare the tea in good spirit, it will taste fine. If they can enjoy tea, everyone can virtually become their own tea master in the process. This is what makes the preparation of tea chan.

Epilogue

I quote Tibor Horváth: „It is certain that anyone who has lived in or visited Japan has encountered more than once this special cult of the tea ceremony. It could not be taken lightly by a serious student of Japanese culture or art history. Any serious attempt to secure a better understanding of it was however hindered by the fact that this requires a prolonged study, namely attending a three years course.”

The three tea masters presented by our blog have deep understanding of tea and decades of experience with it. Tea art is very dear to their heart and with this they can lead other people on the path of cognition. In Tibor Horváth’s person we honour the first Hungarian tea master; Kornélia Rajzó-Kontor’s mission is to pass on teachings of the Urasenke tea school: it is the twelfth course that starts this year, which provides formation to the future generation; Éva Kovács (Hamvaska) is interested in the propagation of tea, following the example of her dear friend and expert on tea propagation Gong Huiying.

Japanese tea art is characterised by order: it is guest Number One who first tastes the prepared tea, it is them who can ask questions and decide on how many cups of tea are to be drunk. Chinese guest welcoming is less formal, more than one infusion is made from the same tea leaves, and it is the tea master who leads the conversation of guests.

The habit of drinking tea, its culture, and the plant itself originate from China, therefore, Japanese and Chinese tea art have the same roots, just like the three main tea schools passing on Sen Rikyu’s legacy. Movements and rules may be different, steps and forms of the ceremony may vary, but the heart [that welcomes guests] is the same.

Gallery

![Female ensemble of Bai ethnic minority of Zhoucheng, Yunnan, reciting Buddhist texts at the Double Ninth Festival [Autumn Festival celebrating the elderly]. (Photo taken by the author)](https://hoppmuseum.hu/files/relatedimages/thumbnails/283.jpg?v=5)