Chinese Collection

The Chinese Collection now holds over seven thousand objects. The oldest pieces date from the Neolithic, while the youngest ones originate from the beginning of the twenty-first century. The collection is especially rich in ancient small bronzes (Ordos bronzes) and jade objects, Buddhist plastic artworks (statues made of lacquer, wood, ceramics, and bronze), ceramics, and twentieth-century paintings and furniture. The largest section of the collection is that of the Chinese ceramics of over 1,500 items, featuring objects from the second century BC until the present day.

Ferenc Hopp set foot in China in March 1883, during his first round-the-world trip, when he bought numerous Chinese goods, which he supplemented during later visits to China in 1904 and 1914. As an optician, he mostly appreciated carved works of gemstone – he especially cherished the carvings of nephrite, jadeite, rock crystal, and amethyst – but had an eye for cloisonné objects, ceramics, and plastic art, too. The collection he bequeathed to the Hungarian state in 1919 contained almost 1,200 objects belonging to the Chinese Collection.

After the Hopp Museum was founded in 1919, the Chinese Collection was substantially augmented with items from public collections in Hungary. Among these were the Chinese holdings purchased by János Xántus during his expedition to the Far East in 1869–1870. During his collecting, Xántus focused mainly on typical Chinese objects from the mid-nineteenth century, works of craftsmanship and cottage industries (paper patterns, rice paper pictures, silk samples, fans, combs, decorative boxes, etc.), and religious objects (statues, altar accessories). The items he brought back from the Orient were exhibited in 1871 in a room at the Natural Cabinet of the Hungarian National Museum. This was the first time that the Hungarian public had seen a large number of Chinese goods (more than 800 of the 2,533 Asian items on display were from China). In the following years, the Chinese Collection expanded by the objects collected by several travellers and collectors (Béla Ágai, Dezső Bozóky, Károly Csapek, István Csók, Ottó Fettick, Lajos Iván, Károly Róbert Kertész, Marcell Nemes, Ferenc Szablya-Frischauf, Vince Wartha, etc.), and art dealers (Sándor Donáth, Mátyás Komor, Géza Szabó, Imre Schwaiger, Vilmos Szilárd).

In the decades between the world wars, art historian Zoltán Felvinczi Takács (1880–1964), the first director of the Hopp Museum, laid the foundation for a representative Chinese collection. His abiding merit is the establishment of a real art collection from the ensemble of interesting and exquisite objects, which, even if still a bit sketchy, today can be used to present the history and representative genres of Chinese art. Felvinczi Takács systematised and thematised the Chinese Collection, classifying the objects into groups according to their materials. During his trip to China in 1935–1936, Felvinczi Takács acquired a ceramic relief of a seated demon from the pagoda of Xiuding Monastery, situated close to Anyang. His friend, professor Albert von Le Coq (1860–1930), one of the leaders of the German expedition to Turfan, gave to Felvinczi Takács, as well as to Pál Teleki, then Prime Minister of Hungary, and to Rafael Zichy, a prominent art collector, fragments of a mural from the Kizil Caves. Two of these fragments now grace the collection of the Hopp Museum. The museum’s holdings of Buddhist sculpture were also substantially augmented with gifts from traders in antiquities. The Hungarian-born art dealer, Imre Schwaiger (1868–1940), whose business activities were based in India, gave the Chinese Collection an extremely rare lacquered statue of Guanyin gazing at the Moon, made at the turn of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

The 1950s saw the establishment of close cultural and artistic relations between Hungary and China, resulting in numerous contemporary Chinese exhibitions being held in Hungary. Almost half of the items (seven hundred objects) presented at one of these exhibitions were donated to the Hopp Museum in 1955 as a gift from the Chinese Central Government. This generous donation, delivered in 22 crates, contained contemporary Chinese pottery from Jingdezhen and Shiwan, as well as lacquerware and cloisonné enamel from Beijing, a variety of textiles and jewellery, ivory and soapstone carvings, and even items of furniture. Its greatest value, however, unquestionably lies in the fact that the gift represents a cross-section of mid-twentieth-century Chinese applied art.

The last major gift came in 1961 when the Chinese Collection was enriched with 321 items of contemporary applied art as part of a Sino-Hungarian cultural agreement. There were numerous exchange visits by cultural delegations from the two countries during this period, which resulted in some important new additions to the Chinese collection, in particular, some modern scroll pictures and album sheets (such as works by Chen Zhifo and Huang Binhong). After World War II, besides the contemporary Chinese gifts, a number of high-quality Chinese antiques also entered the museum’s collection through some major bequests and donations.

Beginning in the 1990s, the Chinese Collection expanded in two main directions. Firstly, the museum’s stock of traditional antiques was augmented with some larger sets of objects (e.g., collections of furniture) and with certain outstanding individual pieces, and secondly, a conscious decision was taken to add to the contemporary collection (for example, with the purchase of ceramics from Jingdezhen).

Gallery

ZHANG GUOLAO

China, 16th–17th century, bronze

Collected by Ferenc Hopp

China, Northern Qi dynasty (550–577)

Painted marble Gift from Marcell Nemes, 1919

China, Turn of the 14th and 15th centuries

Wood, lacquer, and gold on textile

Gift from Imre Schwaiger

China, Late 18th century – first half of the 19th century

Carved, engraved, gilded, lacquered wood

Collected by Ferenc Hopp

China, 18th century,

Teak and rosewood, blue underglaze porcelain, jadeite

Collected by Ferenc Hopp

China, 19th century

Carved and engraved jadeite and wood

Collected by Ferenc Hopp

China, Mid-19th century

Pewter with incised decoration

Collected by János Xántus, 1870

(MUSHROOM OF IMMORTALITY) MOTIF

China, 1426–1435

Blue underglaze porcelain (in Chinese: qinghua) Cobalt Xuande six-character mark

Collected by Ferenc Hopp

China, end of the Neolithic – early Shang period, 2000–1200 BCE

Translucent, pale green jade

Gift from Géza Szabó

China, Eastern Zhou period,

5th century BC

Gilt bronze with carved decoration

Gift from Géza Szabó

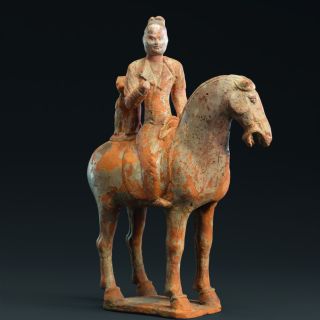

China, turn of 7th–8th centuries

Pressed and moulded red earthenware, coated with white clay paste, with traces of cold painting

China, early 1930s, silk fabric

Estate of Flóra Dessewffy

China, Tang dynasty, 9th–10th century

Sandstone

China, First half of the 18th century

Ink on paper, partly painted with fingers

China, 15th century

Grey porcelain, with pale green cracked glaze (Longquan ware)

Collected by Tibor Horváth

China, 3rd–5th century

Cast bronze, carved, lacquered, and artificially aged

LANDSCAPE

China, Hangzhou, 1952

Ink and colour on paper

China, turn of the 19th–20th centuries

Cypress, bamboo

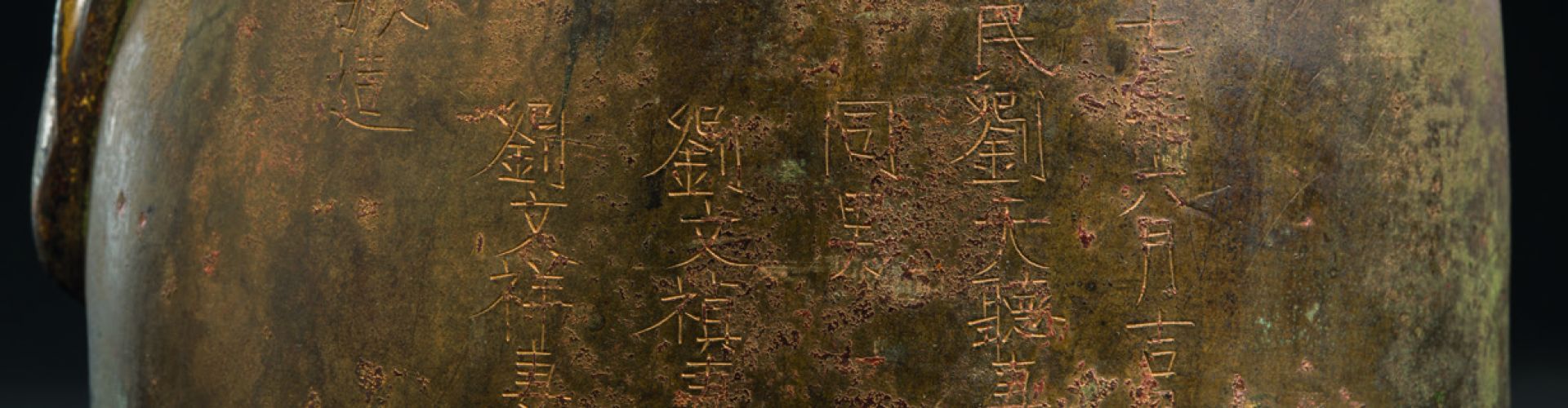

China, dated 1538

Gilt bronze, lacquered

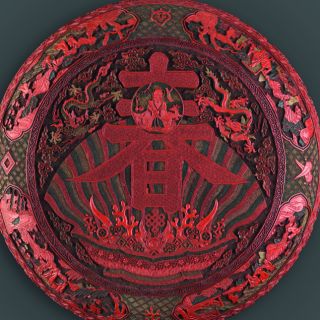

FOR “SPRING”

China, 1736–1795

Carved and lacquered wood

Qianlong six-character seal